We are living in the midst of a truly remarkable moment, one driven by unprecedented technological change. Digital media and technology are now at the very center of all our lives, particularly our children’s. Today’s always-on generation is connected to everyone and everything. Whether it’s through computers in the home, laptops and tablets in the classroom, or mobile devices in our pockets, the boundaries between home and school—and everything in-between—have dissolved. What’s more, kids’ digital lives are starting earlier, impacting practically all school-age kids from kindergarten through 12th grade, at breakneck speed.

We are living in the midst of a truly remarkable moment, one driven by unprecedented technological change. Digital media and technology are now at the very center of all our lives, particularly our children’s. Today’s always-on generation is connected to everyone and everything. Whether it’s through computers in the home, laptops and tablets in the classroom, or mobile devices in our pockets, the boundaries between home and school—and everything in-between—have dissolved. What’s more, kids’ digital lives are starting earlier, impacting practically all school-age kids from kindergarten through 12th grade, at breakneck speed.The innovative and engaging tools that media and technology offer hold great promise for transforming education. But this has put school leaders in a challenging spot, as they try to harness technology for learning while ensuring that kids are using it in safe, healthy, and responsible ways. Among the many things that school leaders and educators already have on their plates, they now also have to manage the competing concerns of parents, teachers, and kids themselves in an ever-evolving digital arena.

Student well-being today is inextricably linked with the digital technologies that run through the middle of kids’ profoundly connected lives. We talk about this new reality as digital well-being, defined as the capacity to look after personal health, safety, relationships, and work-life balance in digital settings.

The Evolving Digital Landscape

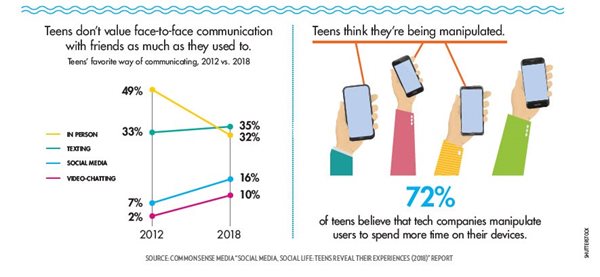

At Common Sense Media, we’ve been researching and chronicling the impact of media and technology on kids since 2003. By far, the biggest concerns we hear today center around how social media and being tethered to digital devices is affecting kids’ mental health and their relationships. According to recent “Common Sense Census” reports on kids’ media use, kids ages 5 to 8 spend an average of nearly three hours per day using screen media, with one hour of that time on mobile devices. Kids ages 9 to 12 spend six hours a day using entertainment media, increasing to nine hours for 13- to 18-year-olds. And our 2018 “Social Media, Social Life: Teens Reveal Their Experiences” report observes that by the time they’re teenagers, 95 percent of U.S. children will on average have their own mobile device to text, play games, post to social media, watch videos, and more. As tweens and teens move into the middle and high school years, they have 24/7 access to friends and peers via apps and mobile devices, with 45 percent of teens saying they’re online almost constantly.And this constantly connected culture can be tough for kids to navigate. From Fortnite, Instagram, Twitter, and Snapchat to Houseparty, TikTok, and the Momo Challenge, there’s a dizzying array of ways kids are engaging online. While there are gender differences in digital behavior—boys are more likely to play video games and girls are more likely to use social media—social media remains one of the most prominent digital forces in kids’ lives. “Social Media, Social Life” also found the percentage of teens who engage with social media multiple times a day has gone from 34 percent in 2012 to 70 percent in 2018. Teens overwhelmingly choose Snapchat (41 percent) as their main social media site followed by Instagram (22 percent) and Facebook (15 percent). But there are hundreds of other social platforms out there, with a new crop emerging every day.

And as these technologies emerge and evolve, how kids are using them seems to evolve even faster. Young people’s digital footprints are increasingly created in tandem with their friends as they casually snap and text like crazy, upload group pictures, and tag each other in posts. On the rise are group text and video apps like House Party, a video version of a chat room that allows up to eight kids to have several livestreaming “parties” together. Long gone are the days of Facebook as a one-stop social platform. Middle and high schoolers periodically discover and migrate to new apps and leverage existing app features in novel ways—for example, using geolocation to track social gatherings in real time, tagging friends who aren’t in pictures so they will receive push notifications telling them they’ve been left out, and managing multiple accounts so that they can intentionally split their audiences. It’s hard for parents and educators to keep up, so it’s no wonder that Common Sense’s most highly trafficked blog posts each year are articles like “Thirteen Online Challenges Your Kid Already Knows About” or “Apps to Watch Out for in 2019.”

Concerns about technology have grown in tandem with its popularity. Grim reports of teen suicide, addiction, eroding social skills, and anxiety and depression have parents on edge. New permutations of cyberbullying and the rise of online hate speech have surfaced in classrooms. Sexting incidents have moved beyond high school to middle school and even into upper elementary in some parts of the country. FOMO (fear of missing out) and image curation affect teens’ self-esteem. Educators complain about digital distraction, short attention spans, and the decreased ability of their students to focus in the classroom. Unfettered access to age-inappropriate online content—featuring violence, sex, self-harm—continue to be deeply concerning to parents and educators alike. And then there are real physical health impacts, such as lack of exercise and sleep deprivation, which can undermine school performance and contribute to depression and anxiety.

Like teenagers themselves, the existing research presents a complex picture that defies simplistic judgments. Much of the research, including that in Jean Twenge’s popular book iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What That Means for the Rest of Us, points to correlations rather than causation. Our own 2018 report “Social Media, Social Life: Teens Reveal Their Experiences,” for example, found that teens feel social media strengthens their relationships with friends and family, provides them with an important avenue for self-expression, and makes them feel less lonely and more connected. At the same time, teens acknowledge that social media can detract from face-to-face communication and make them feel left out or “less than” their peers. That dichotomy is amplified when it comes to more vulnerable teens who score lower on a measure of social-emotional well-being. These teens are much more likely to report feeling bad about themselves when no one comments on their posts or feeling left out after seeing photos on social media of their friends together at something to which they weren’t invited.

Teens are also often depicted as being heedless of the consequences of spending so much time on their smartphones, but our survey reveals that they are fully aware of the power of devices to distract them from key priorities, such as homework, sleep, and time with friends and family. According to “Social Media, Social Life,” 54 percent of teens say their devices distract them when they should be paying attention to the people they’re with, and 44 percent say they are frustrated with their friends for being on their phones so much when they are together. And yet 72 percent of teens feel the need to immediately respond to texts, social-networking messages, and other notifications. “It’s hard to have peace of mind—to truly relax—because even if you aren’t looking at your phone, you know that something is there, a message or an experience waiting to be answered or joined,” says one high school student. “It’s like a parallel universe that you’re carrying around in your head every day. And it’s really stressful.”

And there’s now widespread recognition—even among teens—that technology companies are intentionally designing products to capitalize on FOMO, vie for kids’ attention, and keep them hooked. Behind the apps, games, and social media platforms are teams of designers whose job it is to make their products feel essential. Features such as push notifications are habit-forming. They align an external trigger (the ping) with an internal trigger (a feeling of boredom, uncertainty, insecurity). These calls to action not only interrupt, they cause stress. “Snap Streaks,” “likes,” and messages that self-destruct are just some of the other scientifically proven features that demand kids’ attention right now or make them feel that they’re missing something really important.

Digital Citizenship to Promote Digital Well-Being

Ten years ago, Common Sense helped bring the term “digital citizenship” into the vernacular with the launch of the first comprehensive K–12 Digital Literacy and Citizenship curriculum, which we co-developed with Professor Howard Gardner and the Project Zero team at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Independent schools were also part of our early R&D efforts; Common Sense held informal focus groups with independent school heads in the California Bay Area and Los Angeles to learn about the issues that were surfacing in their schools around kids’ use of digital technology, and we first unveiled our digital citizenship curricular plan at the California Association of Independent Schools’ annual heads and trustees meeting in Los Angeles in 2007.Today more than 700,000 registered educators in 60,000 K–12 schools—independent, parochial, charter, and public—across the country and another 15,000 schools around the globe teach Common Sense’s Digital Citizenship curriculum, which is free to all schools.

In 2017, recognizing the need to address new concerns and challenges for young people in an ever-evolving digital world, we started an ambitious multiyear effort to update and expand our digital citizenship curriculum. We joined forces again with our collaborators at Project Zero to conduct a new wave of research and co-developed the topical framework and pedagogical approaches for a refreshed curriculum. Carrie James and Emily Weinstein at Project Zero surveyed thousands of teachers and parents across the nation to identify key topics of concern. The resulting new curriculum includes six core topics, each guided by an overarching essential question that educators identified as important and urgent: Media Balance and Well-Being; Privacy and Security; Digital Footprints and Identity; Relationships and Communication; Cyberbullying, Digital Drama, and Hate Speech; and News and Media Literacy. Like the original version, the revised curriculum takes a whole-community approach, featuring online lesson plans and student-facing interactives, teacher professional development, and family engagement content, all provided as open educational resources in English and Spanish.

In addition to updating some of the most loved lessons from the original curriculum, we have revised the instructional framework we call the “Rings of Responsibility,” which encourages students to focus on themes of responsibility to oneself (personal dilemmas), to family and friends (moral dilemmas) and to their communities (ethical dilemmas). New lessons have been added based on real-life scenarios that explore digital scenarios in developmentally appropriate ways through video, group discussion, written reflection, and media production. Collectively, these activities help students develop and reinforce the critical thinking skills that are essential to safe, responsible, and healthy behaviors online and positive relationships with technology.

Drawing on long-standing work from Project Zero, a major new thrust of the revised curriculum is to help students develop the dispositions or habits of mind that young people need to make considered decisions as they face digital dilemmas in real time. As one middle school teacher interviewed as part of Project Zero’s ongoing research explained, “I’m not interested in just giving students a definition of sexting, because that’s not going to help them make a decision at 10 p.m. on a Saturday.” Instead, the curriculum incorporates “thinking routines” that help students develop the sensitivity to recognize “red flag feelings” that signal they are facing a tricky digital situation and to practice slowing down and reflecting on their choices before responding. As part of the Media Balance and Well-Being unit at every grade level, students are asked to take stock of their digital media habits with a media inventory, evaluate their emotions, and examine how their different digital activities and behaviors either support or undermine their well-being. They take action by developing a personal media plan with activities they’ve designed to take responsibility for their own media balance.

Through the lens of humane design, middle and high school students deconstruct how certain apps are built to capture and keep their attention and then brainstorm and imagine alternative designs that could help promote media balance. For schools that teach coding and game design, the lessons can be tied to digital media creation activities and prompt ethical considerations among students who plan to pursue future careers in tech. The lessons can also ignite a sense of civic engagement among a broader group of students to put pressure on the tech industry to do better. Teaching students about digital manipulation dovetails with teaching philosophies aimed at giving students agency to redefine their own cultural norms. In high school, students explore the pressure of always being connected, feeling the need to always be available to friends, and how to set boundaries. They learn to analyze the effects of our constantly connected culture on their close friendships and romantic relationships, identifying unhealthy behaviors such as using phones to pressure, monitor, and smother.

The new curriculum also incorporates a research backgrounder and implementation tips for teacher professional development and family activities that parents and students can undertake at home as part of a whole-community approach to building a culture of digital citizenship. In one activity parents and students discuss a “Balance with Bedtime” checklist in which they check statements they can agree upon together (e.g., “We stop using devices an hour before bedtime”). In another lesson, aimed at addressing young people’s frustration about their parents’ disruptive digital habits, students and parents discuss the difference between online and in-person communication (hint: body language, eye contact, and tone of voice). To help parents keep up with the latest technology trends, Common Sense provides weekly tips for parents that schools can incorporate in their newsletters.

Hope for the Future

Despite the challenges that this ever-evolving digital world presents for our children’s health and well-being, there are reasons to be hopeful. Approaching media balance and digital well-being as a family, school community, and a nation means that we’re all in this together. The stakes are high, and we see growing awareness that this is not solely a kid issue but a societal issue, as well as public will to address the problem. Educators and parents are working together to bring digital citizenship into their children’s schools. Policymakers have begun to introduce legislation to fund deeper research on media and technology’s impact on children’s health, such as the $95 million Children and Media Research Advancement (CAMRA) bill. The big tech players (Apple, Google, Facebook), with pressure from consumers, educators, and their own employees, are finally rolling out features that support digital well-being.And we know that schools that embrace robust digital citizenship programs often have a positive and thriving culture around media and technology. We’ve seen independent schools lead the way with innovation and creating a strong culture of digital citizenship. Independent schools can be at the forefront of a paradigm shift that allows them to embrace technology for learning in ways that promote student health and well-being.

How to Embrace Digital Well-Being

Recognizing that digital technology is here to stay and will continue to evolve at a dizzying pace is critical. Schools will need a sustained approach that, by definition, will evolve over time. Consider these guiding principles:- Stay current. School leaders who keep up-to-date on the latest technology trends, research, and technology-related parent and student concerns surfacing in their schools are prepared to address challenges proactively rather than in crisis mode.

- Start early. Efforts to promote digital well-being should continue in developmentally appropriate ways throughout all grades, from the youngest to oldest students.

- Team teach. Involving different types of educators—school counselors, librarians, health, technology, and classroom teachers—in conversations around digital dilemmas leads to richer and more robust teaching.

- Leverage existing programs. Integrating technology topics into existing programs that address student health and well-being can help solve the ever-present problem of too little time in the school day.

- Empower students. Giving students leadership opportunities (peer-to-peer support, social awareness campaigns, or having students learn by doing such as managing the school’s social media account) can deliver positive results.

- Engage parents. A whole-community approach that educates and engages parents, educators, and students leads to the best outcomes for students.

Essential Questions

Common Sense Media has launched the revised digital citizenship curriculum for grades 3–8, and plans to roll out the K–2 and 9–12 grade bands in August, just in time for back to school. There are six topics and guiding questions the revised curriculum addresses:- Media Balance and Well-Being: How can I use media in healthy ways that give meaning and add value to my life?

- Privacy and Security: How can I keep personal data safe and secure and avoid risky situations?

- Digital Footprints and Identity: How can I cultivate my digital identity in ways that are responsible and empowering?

- Relationships and Communication: How can I build positive relationships?

- Cyberbullying, Digital Drama, and Hate Speech: How can I connect positively, treat others respectfully, and create a culture of kindness?

- News and Media Literacy: How can I be a critical media consumer and creator?