Around that same time, the world added another term to the lexicon: disinformation, the purposeful spread of information intended to deceive. We began to see propaganda, hoaxes, fake news, frauds, and images manipulated in Photoshop, all of which has become even more prevalent today. With all the “news” swirling on social media, what’s real and what’s not requires further examination.

As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine wages on, students across America are getting unfiltered access to the realities of war. Many are calling this the “first social media war,” as Ukrainians on the ground share real-time footage from the frontlines. One tweet can spark nationwide aid from a corporation halfway around the world, and simultaneously, misinformation can spread like wildfire. What role do educators play when we see our students and families grappling with complex and potentially dangerous topics like war, misinformation, and even disinformation?

Information Overload

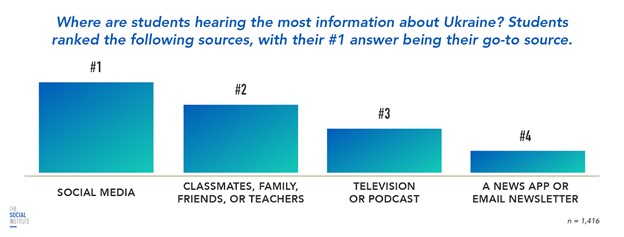

There are 18 million TikTok users in the U.S. who are 14 years old and younger, and users who are older amount to about 20 million. Earlier this month, The Social Institute polled more than 1,400 students in fifth through 12th grade from K–12 independent and public schools across the country to determine where they hear the most information about Ukraine. The top answer was social media. For better or worse, tens of millions of students are consuming information about the war while scrolling their social feeds.

Social media gives us an unfiltered understanding of what’s really happening in Ukraine. A Ukrainian teenage girl has become an unlikely TikTok sensation amid the war. One video, titled “My Typical Day in A Bomb Shelter,” has been viewed 40 million times and shows @Valerisssh hunkering down with her family.

The power of social media can also save lives. Last month, a group of 12th grade students in Winnipeg used satellite imagery and social media during geography class to help a father of one of the school’s teachers flee Ukraine. According to CBC, the geography students used Google Maps, satellite images, and social media to help the man “navigate a labyrinth of rubble and gunfire to make it to the Kyiv train station safely.” When they got the call that he had safely evacuated, the class erupted in celebration. “We were cheering, we were clapping, we were yelling; it was amazing,” said one student.

Meanwhile, social media can expose violent content to young students. Images of dead children lying on a street and injured pregnant women being carried out of rubble will likely be forever seared into the memories of all who saw those tragic and disturbing images. As educators, we have a responsibility to help students navigate this world of snaps, likes, viral posts, and more.

Why Today's Students Need Media Literacy More Than Ever

Every day, students are navigating a media-saturated world, where it can be easy to misconstrue a 280-character tweet or a 9-minute TikTok video. In The Social Institute’s most recent #WinAtSocial LIVE lesson—an interactive learning experience co-created with students and researchers—accessed by K–12 independent and public schools across the country, we presented the following real-life, viral social media posts and asked students: Which of these is accurate and credible?

The correct answer is #3: President Zelensky inviting Elon Musk to visit Ukraine. Only 14% of high school students and 16% of middle schoolers answered our poll correctly.

While the other three images are real, they are either misleading and/or missing context. Here are the true stories behind those images, as originally reported by BBC in an article highlighting misleading viral stories related to Ukraine.

- Post 1: The video claiming to show a Ukrainian girl confronting a Russian soldier is disinformation. The video is 10 years old and shows a Palestinian girl confronting an Israeli soldier.

- Post 2: A video claiming to show a Ukrainian pilot shooting down a Russian fighter jet is a clip from a video game, completely unrelated to the war in Ukraine.

- Post 4: The photo of Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko was taken at a training center more than a year ago, first posted on his Instagram account in March 2021. Although it’s true he has been defending his city alongside Ukrainian troops, this image and caption is misleading.

Help Stop the Spread

Research shows misinformation spreads six times faster on social media than factual stories do, which means misinformation about Ukraine has seeped into students' feeds in and out of the classroom. As the news continues to pour in, we can proactively help our students determine what is real and what is not:- Advisors can play with their advisees two truths and a lie, then segue to discuss how we can vet viral headlines in our feeds.

- Faculty can remind students how to properly assess sources for a class paper.

- Tech-savvy student leaders, like these students at St. Margaret’s Episcopal School, can coach younger students on how to recognize sponsored content.

- Librarians can help students level up their “Google” skills and produce accurate and credible search results as efficiently as possible

It can be easy to fall for fake headlines and made-up stories. To avoid this trap and to consume news responsibly, educators can use advisory, research projects, and peer mentorship programs to coach their students on the following:

Check the facts. Before students share an article on social media, encourage them to fact-check it. Does the article lean toward a particular point of view? Does it link to sites, files, or images that skew to a certain perspective? Does the news story show up on other trusted websites? Does it live on a credible domain, such as .edu or .gov?

Consider the student role. Even though students may be far from Ukraine, there are many things they can do to help. They can fact-check stories before sharing and report to social media platforms any posts that are spreading misinformation or disinformation.

Assess media bias. As a class, check out the Media Bias Chart—created by an independent school alumna—to walk through an interactive chart of where national news publications fall on a spectrum of varying perspectives. Do the findings surprise your students? What are possible consequences if we only consume a narrow sliver of the spectrum?

Recognize sponsored content. A 2016 study found that 82% of middle schoolers believed “sponsored content” was a real news story. Your challenge: See how your students measure up nearly five years since that study. Can they notice the #ad hashtag on sponsored Instagram posts; do they spot the phrase “Powered by” near a sponsored article’s headline?

Avoid emotionally charged and divisive headlines. Do they use powerful words? Do they trigger you to feel fearful, anxious, sad, or angry? Oftentimes, fake news headlines are created to evoke these negative emotions so that we interact with the article and then the creator profits from our click.

Educators have an opportunity to teach positive social media use through the lens of timely, relevant, real-world news—from COVID-19 and the last presidential election to the leaked Facebook files and now Ukraine. And while these current events are ever-unfolding, the skills that we can be teaching our students will be lifelong and timeless.