Unfortunately, much of what’s called global education today focuses on superficial information and token activities that don’t prepare our students to be global citizens. Real global education involves more than hosting festivals with traditional foods, offering world cultures classes in a few grades, or sponsoring an occasional trip abroad. Instead, we must use internationally minded, immersive approaches for learning in and beyond the classroom.

For us at French American International School, a PK-12 school with 1,100 students in San Francisco, global education has been the heart of our mission since our founding more than 50 years ago. To be sure, we benefit from a multilingual, multinational school community and from bilingual, French, and International Baccalaureate programs. But we believe any motivated school can offer an internationally minded education. At French American, we call it cross-cultural cognition — the ability to think, feel, and act across cultures. And we demonstrate this understanding by six touchstones: identity, language study, community, curriculum, global travel, and sustainability.

Identity

We are all citizens of the world — and we all come from somewhere. The foundation of global citizenship is rooted in one’s heritage and identity. At French American, we teach the complexity of identity at all grade levels. Pre-K and kindergarten students reflect on their families’ places of origin and the different lifestyles and living spaces in San Francisco; middle schoolers study the meaning of citizenship in the U.S. and French contexts; and international high school students compare governing systems across the globe in relation to the U.S. model.We aim for students to understand and appreciate identity as a rich mix of national, regional, cultural, ethnic, religious, gender, orientation, socioeconomic, and other factors. This keeps the focus on what we have in common so we don’t become ensnared by differences, stereotypes, and simplifications that incite conflict at home and abroad.

As part of a lower school art project, French American International School students build models of the different ways people live within San Francisco and around the world. Photos are courtesy of French American International School.

Language Study

We believe acquiring competence in a second and then a third language is central to cross-cultural cognition. Languages are loaded with culture, attitudes, tradition, history, etiquette, and more. To learn another language is to gain an alternate perspective, increase empathy, and become open to cultural cues.At French American, a bilingual education is at the core of our PK-8 program. In our flagship International High School, we welcome a large number of students who are not French speakers and who begin or continue second language studies with us. We require students to take four years of a second language to graduate, and during these four years they become fluent due to language immersion in classes, around campus, and on global trips. We devote significant resources to our language programs in Arabic, French, Mandarin, and Spanish.

We also honor our students’ home languages. If we are educating global citizens, we are affirming the value of each child’s identity, including his or her language. At French American, we delight in a diverse set of mother tongues within our faculty, staff, and families, and encourage use of these languages in interactions between both native and non-native speakers.

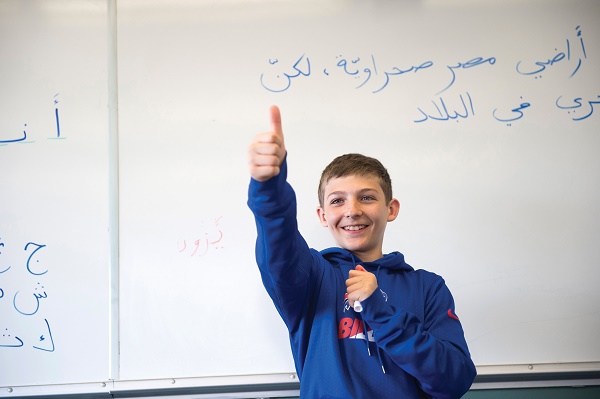

A student learns Arabic in high school as part of second language studies.

Community

Our school’s bilingual and international curricula allow us to hire citizens from around the world. Indeed, many families hail from other countries and choose our school for its international culture. Rather than pushing international faculty members and students to assimilate into our school culture, we encourage them to share their cultures with us. We believe having an educator or fellow student share his or her personal cultural background significantly enriches all students’ experiences.Lower school teachers hailing from England host an annual tea party at our Early Learning Center, guiding our pre-K students to appreciate the international atmosphere of their school through weeks-long discussions and preparations for the event. Middle schoolers in our Arabic and Mandarin language classes do not just learn the language; they are exposed to our educators’ cultures, thereby developing an understanding of different countries’ lifestyles, customs, and attributes. High school students joke with their teachers in hallways, referencing media from native countries that the teachers have shared with students. Some travel to these countries with their teachers in the global travel program.

We celebrate the international diversity of our students and educators.

Curriculum

At French American, we define cross-cultural cognition as the ability to grapple with challenging and abstract concepts from science and math to humanities, social science, and arts in more than one culture. Our bilingual curriculum in grades PK-8 and our International Baccalaureate and French Baccalaureate programs in the high school foster this ability.In a U.S. curricular context, global education needs to be infused in curriculum design. For content, this could take the form of document-based world history and geography, literature in translation, or cultures’ contributions to mathematics. To strengthen classroom culture, teachers can foster cross-cultural cognition through collaboration, appreciative listening, and respectful discourse. In pedagogy, this can mean highlighting the different ways that cultures approach the academic disciplines — and even learning itself.

One high school student, Fatou, compares approaches to literary analysis in French and English:

"I believe that a language is the essence of a culture; and each culture has its own approach to literature. For example, when we write commentaries in French our writing is deep and thorough because it is focused on the quality and depth of the content. Our essays discuss several themes, and each theme is divided into several points that are developed and analyzed in detail. In English, our main focus is on the structure and flow of the argument. So, in essence, by using the techniques from both languages we're able to create elaborate essays, while keeping our writing cohesive and organized. The best of both worlds, in other words."

High school students study histories across world perspectives.

Global Travel

Many schools have travel programs, but to enrich students’ learning, these offerings must combine authentic encounters with other cultures and opportunities for self-reflection.For decades, we have run a Global Travel and Exchange program involving hundreds of students and dozens of teachers annually. Our approach is developmental: Lower school students begin their global travel journey with a sleepover in kindergarten, which helps them understand their community and builds their resilience and autonomy. Students make regional trips of increasing duration in subsequent years. In fifth grade, our students host students from France for two weeks, then travel to their correspondents’ homes for another two weeks, putting their linguistic and cross-cultural skills to work.

In middle school, students travel to the country of the additional language (Arabic, Italian, Mandarin, or Spanish) they are studying; additionally, they complete their bilingual journey with another exchange in France.

In high school, students can take cultural, linguistic, and service learning trips across the globe every year; these have recently included Tahiti, India, the Galapagos Islands, Jordan, Senegal, Austria, Guatemala, and Malawi.

Many schools might ask: What are the benefits, and can they possibly outweigh the costs and risks involved? We find our students answer these questions best. Here is Gwyneth, after her cultural study trip to India:

"No matter where we were, be it the slums of Mumbai, or the rural areas of Hyderabad, the people were so full of life and culture. They are what made the country so beautiful. Their enthusiasm to bring us into their world, even for a brief moment … is what made this a cultural immersion. My eyes have been opened to culture like never before. You can read about the slums, listen to the music, watch a Bollywood dance film, but only when you're there, doing it all, do you truly learn and become an international student."

For global learning, it’s clear that nothing beats being there. But schools in which such travel is not sustainable can foster international encounters — by hosting international exchange students, engaging in digital pen pal relationships, and collaborating via Skype and other technologies with peers in other places. With reflection and context, these encounters can spark interest in various cultures and engender empathy for their citizens — impulses that contribute to global understanding.

Young students in Mumbai share songs and games with International High School students during a service learning trip to India.

Sustainability

A critical marker of a global education is a sense of responsibility for our shared planet. We make it clear at every grade level that students’ local decisions have a global impact.Our youngest students plant urban gardens of pollinator targets, a project that opens their eyes to the sharing economy of insects and plants, and delves into the ways these actions matter for our planet’s future. In middle school, students build green architectural models designed to reduce carbon dioxide, harvest rainwater, and generate solar energy. High school students continue their studies on climate change, exploring population dynamics and biodiversity in and out of the classroom to deepen their understanding of stewardship. When 12th-grader Wesley traveled to the Galapagos on a science trip, he remarked on the deep impact of globalization:

"I realized that most of the island is inhabited by thousands of people. This was a shock to me to see roads, cars, and conveniences stores, just entire communities on the Galapagos Islands... I really took into consideration the fragility of the natural environment and understood the globalization that is happening in every corner of the world."

Educating students about sustainability also highlights the value of collaboration. Even within the classroom, students must work together to grow, design, and build solutions. As the curriculum evolves, that collaboration expands to a world perspective that has roots in their first-grade urban garden.

Lower school students work in their urban garden.